DAILY, EXCEPT SUNDAY

By Pete Martinez

Kerrville was a center for the wool and mohair industry and sheep and goat ranchers from the area shipped their products on the little train that chugged into town every day around noon. The various stories that supplied those ranchers and the citizens of Kerr County received many of their goods on the train. Old timers talked about the days the train came seven days a week. The Sunday trip was stopped when all the churches protested the interference with their Sunday services. My mother and father were both school teachers and it was there, in Kerrville, that they developed an interest in photography that rubbed off on me. There were many hours spent in the darkroom watching those images appear as the paper was gently swished back and forth in the developer. Of the many photo subjects, my favorite was the railroad and now I can look at those old photographs, made with a Speed Graphic, and reminisce about the beginnings of my interest and love in the old iron horse.

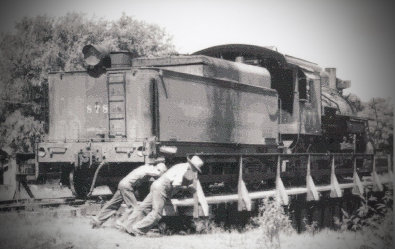

When I was in grade school some of us boys (I donít remember girls being interested in trains) would walk all the way to the end of the line on Saturday, during the school year, to watch the train crew turn the engine around. During the summer it could be any day, except Sunday of course. The engine would stop on the siding, uncouple from the cars, and move on down to the manual, Armstrong, turntable which was at the western end of the branch line. It was interesting to watch the engineer run the big 2-8-0 Consolidation steam engine onto the turntable, moving it forward and backward until he got it balanced just right. Then the brakeman would pull the alignment bar from between the rails and we would help by leaning on the beam to get the table moving. The brakeman knew just where to stop pushing to let the table, and its load, coast to a stop at the right point to align the turntable track up with the spur. The alignment bar would be put back in place and the engineer would move the engine off and start switching the cars. It would take about an hour and a half to set off the incoming cars and pick up all of the cars that would be in the return train to San Antonio.

There was one Saturday when two of my friends and I reached the turntable and found the train was late. We could hear the whistle so we knew it was coming, but it seemed it was taking forever to get there. When we saw it finial rounding the curve about a half mile away, there was another of our friends jogging in the middle of the track in front of the engine. The engineering was pulling on the whistle cord trying to get the young boy to move off of the track, but no avail. Our friend finally left the track and disappeared into town. This particular friend had a tendency to do crazy things with the train; throwing rocks at the conductor, or brakeman, when one of them would stuck his head out of the caboose window was one of his favorites. He never hit them but it would make the target pull his head back in and shake his fist at the youth. Getting in the spirit of the game I took an egg and hid it away for about a week to get it real rotten. I waited until the train was crossing the road a block from the house. Losing my nerve, I threw the egg at a box car instead. I was so excited I threw the egg clear over the car and it landed harmlessly in the grass on the other side.

During the war, the Army Transportation Corps set up a training facility in Kerrville to instruct soldiers that were going to the various Army Railway Battalions in right-of-way maintenance. The men worked on replacing ties, tamping ballast, and replacing bridge timbers. They had a small crane and a few little flat bed rail cars to carry barrels of spikes, tie plates, and tools. They pulled the crane and rail cars with a motorized hand car that we called a putt-putt. Once and a while, one of us would place a penny on the rail, hoping that it would be flattened by the locomotive pulling the daily train. This was to tame for our wayward friend who got a little inventive one day and almost caused a disaster. Rather than a penny, he put a rail spike on each of the rails. We retreated into the woods and waited for the train to come. We didnít have long to wait but it wasnít a locomotive that found the spikes. One of the putt-putts, with three men on it, was sailing down the track and when it hit the spikes it left the rail for about ten feet. It landed back on the rails and came to a stop. The soldiers got off and looked everywhere for the culprits that had made them join the airborne. Luckily, we were able to remain quietly hidden in the woods until they left.

About a block from our house the tracks crossed a small creek on a timber bridge that to a small boy was a huge, high, trestle. Crossing the bridge on our way to school was the highlight of our day. Some years later I returned to Kerrville has an adult and walked down the right-away to look at this monstrous trestle of my youth. As I stood in the dry creek bed I could reach up and touch the timber beams that spanned the four foot wide creek. The rails where no more than 14 feet above the creek bed. Objects seem to shrink as you get older.

We moved away from Kerrville in 1947. On return trips I found that mighty steam giant, the consolidation, had been replaced by a diesel engine. No more sound of the whistle with the personality of the engineer and watching the progress of the train from the smoke billing in the air. No more action of the drive rods and valve gear. For a few years there was the monotonous drone of the diesel and the blaring of the horn to announce the arrival of the train. Now I-10 passes three miles north of where the turntable stood and all of the towns freight is hauled in and out of Kerrville by truck. There are no more gleaming rails leading off to the southwest and only a hint of the right-away remains. But I can look at those old photographs and Iím a kid again back in Kerrville with nothing to do but meet the train around noon and help push that old turntable around once more. Those were my ďgood old daysĒ.